This period saw significant changes in the department and in the BBC itself. In the summer of 1990, Mark Wilson departed and was replaced by Tony Morson, the second member of staff to be appointed from outside the Corporation. In the spring of 1991, Pete Thomas, the author’s line manager, successfully sold a pair of his company’s high-powered and high-quality loudspeakers to the Corporation for £10,000. Having done this, he bravely left the BBC to develop his new business.

The author, on his return from Radio Projects, was advised to take a higher profile and began issuing progress reports. One new duty involved taking recently-recruited staff on a tour of the Workshop. On one such visit a secretary asked about the loudspeakers. The author said ‘They’re Roger’s.’ to which she replied ‘Does he work here?’. It was impossible not to say ‘Do you know him?’.

The summer of 1991 was rather amusing. Dick Mills, in usual form, opened a carton of rather well-matured yoghourt that exploded, causing the entire contents to fly over Ray Riley’s jacket. And Guy, the canteen chef, burned his face with hot custard. He had to use an ice pack but got little sympathy as everyone kept laughing. Ray Riley, having arrived on a horribly wet day, hung his umbrella up to dry. That evening, he discovered that Malcolm had filled the umbrella with polystyrene packing chips. The next day he got his revenge: he filled the entire drawer of Malcolm’s desk with even more chips!

And the nasty smell emerging from Room 6 was found to be decomposing glue on old tape labels!

By the summer of 1991, John Birt had been appointed as Director General of the BBC. In November of the same year, the Corporation launched a two-pronged initiative that was ungrammatically known as Producer Choice. In this, programme-makers would be encouraged to use the services of outside companies, whilst ‘in-house’ departments would become ‘business units’ that had to create enough revenue to cover their operating costs. In the process, the Corporation would shed around 8,000 jobs.

On the surface, this seemed similar to the introduction of ‘market forces’ in public services, such as ‘competitive tendering’ used by councils. However, closer examination revealed that Producer Choice was designed to consign ‘non-core’ parts of the BBC to the scrap heap, whilst leaving management free of blame. Many departments couldn’t cover their overheads, some of which were outside of their control. Worse still, their customers and profits would be siphoned away by outside agencies.

Being at the edge of BBC activities, the Workshop was to become a business unit. Although each composer generated enough revenue for a comfortable lifestyle, there wasn’t enough money for the maintenance, heating, lighting and security of a building such as Maida Vale. Worse still, although project money could be borrowed from central funds, it would have to be paid back, with interest.

The Radiophonic Workshop had five years in which to break even. It didn’t make it.

As Macintosh computers developed, so the Mac Operating System (Mac OS) changed. Until now, most versions of the Mac OS, known as the System, were compatible with earlier software. Unfortunately, System 7, with its improved user interface, didn’t work with many older applications.

The biggest problem was HyperCard, the application used for Cue Card. Even before System 7 appeared it could be rather unpredictable, sometimes overwriting files on its own accord. However, in its original form it was incompatible with System 7 and newer versions didn’t support MIDI at all. The author assumed, perhaps wrongly, that Apple’s failure to accommodate MIDI or to develop its MIDI Manager software was a consequence of its legal battle with the Apple Corp record company. Following an out-of-court agreement, Apple certainly seemed to lose interest in computer music.

HyperCard’s demise was discovered by Tony Morson during investigations in the autumn of 1991. At the same time, he tested Max, his application for controlling DP3200 matrixes. Unfortunately, this wouldn’t work either, since System 7 came with a newer version of MIDI Manager.

Once Cue Card had departed, most machines in the Workshop moved on to System 7 whilst the composers began using StudioVision as their main sequencing application. Most composers didn’t actually work with conventional musical notation, although this was possible with Mark of the Unicorn’s Composer, an application ‘tied in’ with MOTU’s Performer program. However, in 1992, Peter Howell experimented with an alternative musical scripting application known as Encore.

Once Studio F had settled into using StudioVision, Peter Howell converted Elizabeth Parker’s DAT and S550 ‘library’ files into the new HyperCard format. Unfortunately, this also had problems, so they had to be transferred into ClarisWorks databases. In fact, ClarisWorks, the general-purpose word-processing, drawing, painting, spreadsheet and database application, was installed in all the studios. Although the engineers had previously used MacWrite II for word-processing and MacDraft 2 for drawings, ClarisWorks replaced both applications, as well as Excel and Microsoft Works. The main office, however, retained an Omnis database for the Workshop’s recording library.

During 1991, various applications, frequently used in unorthodox ways, were removed from the studio machines. For example, a list of Emu sounds in Studio C, as kept in Borland’s Sidekick, was transferred to another small application known as Address Book. Other unnecessary applications, such as Omnis, were also eliminated to remove any problems they might cause. This was important, as older applications weren’t always ‘32-bit clean’ and could upset a Mac with over 8 MB of RAM.

To everyone’s annoyance, many of the applications used by the Workshop, including the Studio 5 software, came on a installer disk that used ‘key disk’ copy protection. This permitted the owner of the software to make a limited number of installations from the floppy disk, although usually an ‘illegal’ copy of the application could also be enabled by inserting the disk. Once, when Ray Riley used a Studio 5 disk too many times, the computer merrily played ‘Be-bop-a-lula, She’s my Baby’!

To get around this problem, Ray created an ‘image’ copy of each new installer disk. This could then be used to make a replica of the disk that would work in the same way as the original. By the summer of 1992 he was using a stack of four 100 MB drives for such purposes. Around this time, a new version of StudioVision appeared, accommodating SMPTE timecode ‘markers’ and allowing music to be edited whilst it was playing. Ray Riley discovered that this application required the Serial Switch control panel, as supplied with the Mac IIx computer, to be set in ‘compatible’ mode.

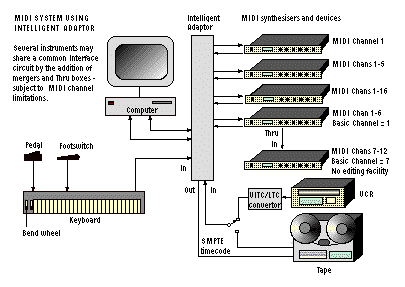

Early in 1992, experiments were conducted in Studio D (now the Workshop’s ‘test’ area) on the new Opcode Studio 5 MIDI interface. This was tested with Yamaha TX816, TX802 and TX81Z synthesisers, as well as an Akai DP3200 matrix. The Studio 5, unlike older interfaces, gave fifteen separate MIDI input and output circuits, a total of 240 individual MIDI channels. All of these circuits could be ‘patched’ via the Opcode MIDI System (OMS), later known as the Open MIDI System.The diagram below shows how devices were wired to an intelligent adaptor, such as the Studio 5:-

OMS was an entirely new protocol. Whilst HyperCard and older sequencing applications had used a system known as Standard MIDI, this didn’t allow for interaction between MIDI applications, which meant that quitting or switching between applications could upset the interface. To avoid this problem, Apple had developed a system-wide protocol known as MIDI Manager. Although this was only available to applications that supported it, Standard MIDI applications could still be used. MIDI Manager was accompanied by a special utility known as PatchBay, which allowed MIDI information to be directed to and from either serial port on the Mac or between different MIDI applications.

Unfortunately, both Standard MIDI and MIDI Manager only supported older MIDI interfaces that conveyed a single MIDI circuit over each Mac serial port. The new OMS protocol was designed for interfaces such as the Studio 5 that could transfer data from multiple MIDI circuits. This was achieved by using higher transfer speeds and by ‘packaging’ the data for each circuit within unique codes.

Although the older forms of MIDI management software could use the Studio 5 interface, there were serious limitations. For example, MIDI data sent from a Standard MIDI application would appear on every output circuit on the Studio 5. However, with an application that used MIDI Manager, the MIDI data would always go to a MIDI circuit that had been preselected in the OMS software. Only applications that supported OMS could direct MIDI data at any time to any output of the Studio 5.

The biggest problem was Performer, an application used by some composers for MIDI sequencing. If used with the Studio 5 when emulating a MIDI Time Piece, it prevented other applications from using MIDI Manager or OMS. This problem suggested that the Workshop would have to continue using the StudioVision sequencing application wherever Studio 5 interfaces were adopted. At the same time, alternatives to HyperCard, such as the Galaxy editing application, would be necessary to transfer material between a computer and other devices, including DMP7 mixers and samplers.

Tony Morson’s first challenge was to get the output of Max, his matrix control application, into OMS. The best method was to use PatchBay to direct its data to MIDI Manager and thence into OMS. Consideration also had to be given to the actual MIDI messages sent to the matrixes. With the Opcode Studio 3, the matrix instructions had been wrapped in ‘dummy’ bytes that made each look like a standard ‘system exclusive’ MIDI message. But the MIDI Time Piece, when installed in Studio X, had objected to these exclusive codes and the instructions had been modified yet again. Strangely enough, the Studio 5 also required messages in the form used by the MIDI Time Piece.

By the spring of 1992, Tony Morson had developed an improved version of Max. This included Peter Howell’s original idea of an ‘addset’, a set of additional matrix connections that could be overlayed on top of a standard setup. Tony’s new version of this was known as a QuickPatch.

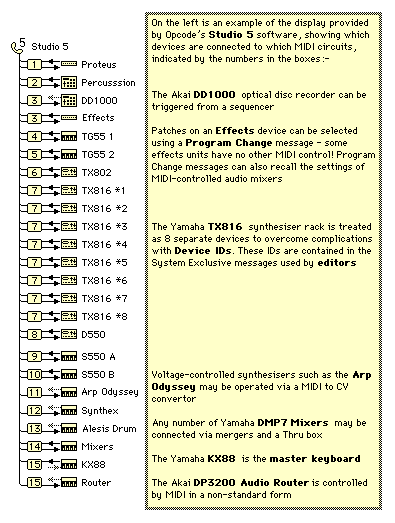

Five Studio 5 interfaces were soon in use. A typical setup is shown below:-

In this diagram, the DP3200 matrix is actually called an ‘audio router’, pronounced ‘route-er’. The instrument list was usually expanded to contain a dummy instrument, often known as Z-dummy. This provided a ‘dead’ destination that could be used for ‘laying’ MIDI tracks without creating any sounds. It also prevented DMP7 mixer data from getting back into the synthesisers as note information. If MIDI ‘feedback’ was allowed to occur around a DMP7 the faders would feel rather ‘rubbery’!

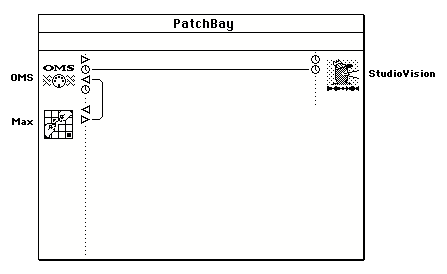

The next screen shot shows how data from Tony Morson’s Max application was directed into OMS from within PatchBay. Timecode information, shown by the little ‘clocks’, also had to be directed via PatchBay to get it from OMS to the StudioVision application.

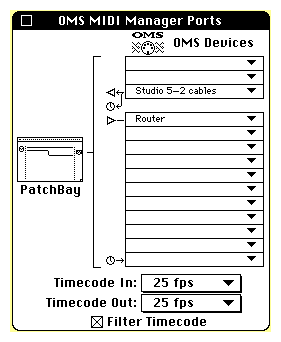

The corresponding setup in OMS is shown below:-

The popup marked Router sent the output of PatchBay, already fed from Max, to the matrix. In addition, timecode was directed from OMS to PatchBay. This appears by the popup item marked as Studio 5—2 cables, which means the Studio 5 was connected to both serial ports on the Mac.

Quirks were found. For example, each DMP7 mixer often produced a ‘glitch’ of data that could be accidentally ‘auto-channelised’ back to the MIDI channel being recorded by a sequencer. This problem was easily fixed. If the AUTO button on the DMP7 was pressed, the mixer would process instructions received via MIDI differently to those generated by manual operation of the mixer’s controls.

Elizabeth Parker in Studio F suffered from ‘sticking notes’, caused by sending music at 280 clock beats per second and timecode via MIDI Manager. Tony turned off the Mac’s RAM Cache, which helped. But then Ray Riley discovered that the Studio 5 didn’t like receiving MIDI data at more than 1.4 times the standard MIDI rate. This was odd, since the device was meant to accept data at eight times the rate and could generate data at the highest speed. Eventually, he set up the interface to work at only twice the normal input rate and six times the output rate. This seemed to cure the problem.

And in Studio H, three MIDI devices were correctly connected via MIDI Thru sockets. But the equipment wouldn’t work properly until connected via a V10 ‘thru box’.

The rapid developments in microprocessor technology meant that high-quality synthesisers were now available at very low prices. One of the most impressive devices was the Emu Proteus, demonstrated at the Workshop in September 1990. This was effectively an ‘orchestra in a box’, containing around 300 sounds, sixteen of which could be played at once with 32-note polyphony. By the end of the year, both Studio B and Studio H had these devices, the latter replacing the older Yamaha TX81Z.

Another low-cost device, the Proformance Plus also appeared at this time, along with the Alesis Quadraverb, a small digital reverberation device. In common with other ‘economy’ products it used a ‘battery eliminator’ for the power supply. Fortunately, its power unit was fitted with a DIN plug, which meant that it couldn’t be used with anything else. Yamaha and Roland, however, employed a ‘universal’ low-voltage plug, but each company used the opposite polarity. Luckily, a Roland TR707 drum machine didn’t come to grief when it was accidentally connected to a Yamaha power supply!

The Lone Woolf MIDI Tap was an unusual device that allowed MIDI data to be conveyed over distances of up to a kilometre (km) via fibre-optic cable. Despite its apparent usefulness, it never came out of the cupboard! The handheld MIDI Analyser was a handy device for the engineers, since it displayed MIDI data in full detail. A Yamaha TG55 synthesiser was also obtained at this time.

Early in 1991, Mark of the Unicorn loaned the Workshop its new MIDI Mixer, a seven-channel audio mixer with auxiliary inputs and outputs as well as a ‘chaining’ ability. Although useful for a small studio, it couldn’t compare with a DMP7 and its real faders. Later that year, Procussion drum machines were added to Studios C and F, whilst the old Roland D50 keyboard was removed from Studio F. In the spring of 1992 an Oberheim Matrix 1000 synthesiser was also installed in F.

Early in 1993, new Emu and Roland samplers arrived, all with Mac software for editing sounds.

Despite being in use for some time, the circular consoles continued to evolve. Early in 1991, the individual outputs of the TX816 synthesiser in Studio B were again connected directly to a matrix, whilst the new Proteus synth was connected to the inputs formerly used for the 8-track tape machine. At this time, Peter Howell was working on an American co-production. This meant that he had to use a NTSC form of U-matic video machine as well as a Barco video monitor that would accept signals at 30 frames per second. As usual, there were problems with the provision of VITC tapes.

Although a vital to the studio, the Akai DD1000 digital recorder caused complications. For example, software for controlling it via a Mac’s SCSI port didn’t work, even when the DD1000 was fitted with a new ROM. Like most disk-based devices, the machine was rather noisy. So, in the autumn of 1991, it was moved to a lower cupboard, fitted with a glass door so the level indicators could be seen. Sadly, this new door didn’t stop the sound from escaping, so the original one was restored. At the same time, the U-matic VCR was moved from beneath the television monitor and into one of the mini-racks.

A Yamaha SPX1000 effects device, with digital connections into the main DMP7D, as well as a new Bel delay unit, were also added to the installation. Early in 1992, the two ‘halves’ of two PCM2500 DAT machines were separated to allow both machines to be squeezed into one mini-rack. The ‘transport’ section of each machine was put in the rack whilst the ‘interface’ portion was relocated in a lower cupboard. The two halves were then linked together by means of extended cables.

By the summer of the same year, the monitoring unit software was updated to accommodate the extra DAT machine and other major changes made to the wiring. Sadly, Red Ryder, the application originally used for downloading the software from the Mac, was incompatible with System 7, although the ‘communications’ elements of the newer ClarisWorks office package worked perfectly.

Meanwhile, in Studio F, Elizabeth Parker wanted to use an RX5 drum machine to create a ‘click track’ for timing purposes, but also needed the Procussion that shared the same MIDI circuit. The solution, as suggested by Peter Howell, was really simple. The RX5 was assigned to the very top note of the scale whilst the Procussion was instructed to ignore the same note. In StudioVision, ‘Metronome’ was made to operate the top key of the MIDI circuit that was labelled as ‘Drum Machine’.

Towards the end of 1992, several modifications were made to Studio F, including the removal of most of the ‘bridge’ circuits between matrixes, so increasing the number of available inputs and outputs. In addition, Ray Riley completed construction of a spare Custom Interface Unit (CIU). Unfortunately the CIU in Studio F suffered from very intermittent clicks and level offsets, clearly due to a ‘misalignment’ of audio data bits. This problem was never really resolved, although Elizabeth Parker was instructed on how to adjust the digital pad on the main DMP7D to eliminate the offsets.

SoundTools Pro, although useful, was too expensive to fit in all studios. Early in 1991, Digidesign created a new low-cost system known as AudioMedia, consisting of a single NuBus card with audio connections provided on phono and jack sockets. Special AudioMedia software allowed sound samples to be captured, manipulated and stored on a Macintosh. Best of all, the card could play two-track sounds within a StudioVision sequence. AudioMedia cards were soon installed in most studios.

In 1992, a new version of AudioMedia software was introduced. However, this didn’t work until the ‘Sample Rate Folder’, as supplied with the latest Sound Designer software for SoundTools, had been added. In the same year, a new Digidesign card known as ProTools was installed in Studios D and F. This card gave a four-channel output, although it only had two input channels. Better still, any number of channels could be provided by simply adding extra cards. SampleCell, a sampler built onto a NuBus card and supplied with matching Macintosh software, also appeared at this time.

In the autumn of 1992, the author was sent on a Mac Survival Course, even though he was due to leave the BBC in less than six months!

By the spring of 1991, the original 40 MB drives in the Mac IIx computers had become totally inadequate. Syco Systems then attempted to install 200 MB replacements, but found that all the space was taken up by the original drive and that the machine had an incompatible drive power connector. By the summer, alternative Seagate drives were fitted into all seven ‘studio’ machines. Just one year later, four of these drives failed completely. Curiously enough, the HD Toolkit software identified the drive, not as a Seagate, but as a CDC 1239N, whatever that was. Closer examination showed that the ‘problem’ drives had different components and extra blue wires fitted to the printed circuit boards!

Also in 1991, the old Mac Plus computers were sent into well-deserved retirement, although two of them continued to provide service in Television Sound. Meanwhile, the engineers obtained a second Radius monitor and a further 4 MB of RAM for their SE/30 computers. At this time JL Cooper’s CS-1 Control Station was introduced to the Workshop’s studios, connected to the Mac via its Apple Desktop Bus (ADB), the same port used for the keyboard and mouse. It contained programmable buttons and a wheel that could be set up to control chosen functions in any application. Snooper was also useful, consisting of software for testing Mac hardware and a NuBus card fitted with LEDs.

Early in 1992, consideration was given to replacing most of the old Mac IIx machines by a newer model. Whilst the IIx contained a 68020 processor, ran at 16 MHz and was limited to 8 MB of RAM, the latest Quadra 900 had a 68030 device incorporating a floating point unit (FPU), ran at 25 MHz and could be fitted with up to 256 MB of RAM. Although the clock speeds of these machines seem horribly slow by modern standards, the simpler system software of the time ensured they were reasonably fast. And, as with many computers, the real speed limitation was often set by the hard disk drive mechanism. Interestingly, Cue Card wouldn’t work on a new Quadra 900, even under System 6, although this machine happily accepted newer software. In March, five of these new computers arrived for the studios, along with a smaller Quadra 700 for Tony Morson. As a sensible economy, the RAM modules from the old Mac IIx machines were transferred into the new computers.

The first magneto-optical (MO) disk drive also arrived at this time. Supplied by Syco and manufactured by Sony, it provided 128 MB of storage on a 3½ disk that looked similar to a floppy disk. Initially, the drive was connected to a Mac IIsi, but didn’t work until all unnecessary system extensions were disabled, the formatting software was changed and virus-checking completed. Despite this sorry start, this kind of disk was exceptionally reliable and extra drives were later obtained.

At the end of 1992, the Mac SE/30 in the main office was replaced by a Mac IIfx whilst Brian Hodgson used a PowerBook with a MO disk drive. Unfortunately, the two Mac IIsi machines originally assigned to these areas couldn’t cope with the Workshop’s Omnis database.

Before 1990, most Workshop computers were connected to an AppleTalk network, later known as LocalTalk. This was horribly unreliable, mainly due to the flimsy connectors used on the LocalTalk connection boxes. The cabling on the network was also excessive, which led Rupert Brun, during his attachment, to abandon the system. From now on, any kind of network was known as a ‘not-work’!

A vestige of this LocalTalk system was retained between the office areas and the engineering computers, although by the autumn of 1991, this had been replaced by a ‘thin’ Ethernet system. Unlike modern machines, Macs didn’t have built-in Ethernet ports. Worse still, the only expansion slots in the engineer’s SE/30 computers were occupied by Radius video cards. To provide Ethernet, the latter were fitted with Novotech EtherPrint boxes, connected to each machine’s SCSI port. Since Brian Hodgson’s PowerBook didn’t have any expansion ports, this too had to be connected via SCSI, this time with a Dayna interface. Other computers needed an Ethernet card (the Mac IIsi required a particularly difficult card) as well as a ‘media adaptor’ for the actual network wiring.

Having set up the system, ‘alias’ files were created on each computer’s desktop, giving instant access to designated folders on the drives of other machines. Although Ethernet was used for file transfers, the original LocalTalk network was retained for those printers that didn’t have an Ethernet port.

By the autumn of 1992, plans were afoot to join up the Workshop’s Ethernet network to Maida Vale’s new Central Traffic Area (CTA), located near Studio 7. This would allow access to Broadcasting House (BH) via Novell’s Netware software. To accommodate this, each Mac had to be equipped with SoftPC and SoftNode software, although there were some doubts as to whether SoftNode would work via the Novotech Ethernet adaptors on the SE/30 machines. The ‘AUTOEXEC.BAT’ file, as used for starting PC emulation on the Mac, had to be modified. This was the author’s first, and hopefully last, experience of an absolutely dreadful text-editing application known as EDLIN.

Digital sequencing and recording equipment was now beginning to oust conventional analogue devices. However, older equipment remained in use, if only to play existing recorded material. For example, in the spring of 1991, Roger Limb remixed a recording created in 1976. In the same year, Richard Attree needed a 24-track machine in Studio H, but a Studer A800 wouldn’t fit through the door, so he had use a machine from another Radiophonic studio! And in 1992, Malcolm Clarke used his 24-track with timecode generated by his Studio 5 interface. Even so, a Studer A80 16-track, A80 8-track, and the quarter-inch A80 VU from the Film Area in Studio F went to Redundant Plant.

In the autumn of 1991, two DTC1000 Pro DAT recorders arrived. These were similar to the original Sony DTC1000, but accommodated ‘studio level’ signals without any modifications. They also recorded digitally at 44.1 kHz, unlike older machines where this had been blocked to stop ‘pirate’ copying of CDs. Two original DTC1000 recorders were also modified by HHB to permit recording at either 44.1 or 48 kHz. All studios now had two DATs, usually wired together for digital copying.

As with quarter-inch tape, the Workshop recorded onto DAT at a level that was around 4 dB higher than the rest of the BBC. None of the composers seemed to notice this, apart from Richard Attree, who observed the difference whilst compiling material for a programme in the summer of 1992!

In the winter of 1991, Alesis announced a new 8-track digital recording format, known as ADAT. This used standard Video Home System (VHS) video cassettes and was reasonably priced at £3,000. It also had a pair of optical connectors for digital audio connections, one for all the recording circuits and the other for all the replay signals. In addition, it had a 9-pin synchronisation connector that allowed a computer to control the transport mechanism. A sample machine was tested in the summer of 1992 and was found to be excellent in every respect, although the outputs dropped by 6 dB when connected to unbalanced destinations. ADAT, which was eventually adopted by much of the music industry, replaced the older analogue formats throughout the Workshop during 1993.

In the spring of 1992, the Workshop was involved in an electro-acoustic concert at the new Broadgate development in London, as well as the Cathedral of Sound at the ‘new’ Liverpool Street station. To do this, Peter Howell copied quadraphonic material from four tracks of the 16-track in Studio F onto two DAT machines. To synchronise the start point for playback, he recorded a ‘blip’ at the start of recording on both machines. The material was also transferred onto his DD1000. The results, especially the ‘electronic birds’, were appreciated by many of the station’s travel-weary commuters.

Around this time, the Workshop installed a facility for making Compact Discs in Studio D, incorporating a Micromega CD-R drive, developed by Philips and modified by Audio & Design. This was accompanied by an Audio & Design Smart Box that extracted the ‘DAT track codes’ from the S/PDIF signal provided by a PCM2500 DAT machine and converted them into ‘CD tracks IDs’ for the CD itself. Curiously enough, this wasn’t possible via the professional AES/EBU digital interface. The S/PDIF signal also gave an effective 6 dB boost in volume, ensuring a ‘commercial’ recording level on the CD. In the summer of 1992, an Audio & Design Limiter, identical to that in Studio X, was added to the installation. As with the other unit, this was modified to have a threshold 5 dB above the normal +5 to +15 dB value. When set to a limit of 4 to 6 dB, a very good recording level was obtained.

The Workshop also needed to play those old-fashioned things known as records. By this time, all the studios had a Technics SLP1200 turntable and a Surrey Disk Amplifier contained in a mobile trolley. However, in 1990, Studio D still used a Corporation-designed twin-turntable known as an RP2/9. This was soon replaced by another SLP1200, this time connected to an EMO pickup amplifier.

Compact Cassette machines were also used extensively, often providing producers with a sample of the composer’s work or employed for studying other source material. In a few instances, when original material was lost, cassette recordings would even be used to create broadcast material. Very low-cost Sony cassette machines were used, modified with a 10 dB output amplifier to ensure that the output level was closely matched to that at the input. Unfortunately, these machines used conventional lamp bulbs, soldered into place, for the ‘motion-sensing’ circuitry. This meant that they stopped working at the most unfortunate times. By 1993, these machines certainly needed replacing.

During this period, the BBC introduced a very rigorous approach to safety. For example, in 1990, Rupert Brun had begun assembling a special headphone amplifier for use in the acoustic area. This was fitted with red, amber and green indicators that showed whether on not the sound level was within safe limits. If the user allowed the red indicator to stay illuminated they risked damage to their hearing.

Tests were also made on the monitoring levels used with loudspeakers. The author correctly guessed the level to be 75 dB Leq, a very modest volume compared with pop music studios. In fact, the Workshop couldn’t use high monitoring levels because of the poor acoustic isolation between studios.

Every studio was now regularly checked for electrical safety. This involved disconnecting each device from the studio system and then checking both the insulation resistance and earth circuit impedance.

In the summer of 1992, it was found that the traditional practice of breaking the earth link on 13 amp sockets (which prevented the technical earth getting in contact with the general services earth) was a safety hazard. Removing this link weakened the structure of the earth contacts and caused them to fall backward, leaving the outlet without any earth connection. To overcome the problem, new unmodified sockets were fitted onto plastic boxes, ensuring insulation between the two earthing circuits.

In addition, the BBC’s XLR-LNE connector, as used for connecting a ‘detachable’ mains lead to a device, didn’t conform to any known British Standard. Barry Baker, then the author’s line manager, advised that they were not to be used by operational staff. Hence, many older devices with this odd connector were modified by fitting a cable gland and attaching a fixed mains cable. Several outdated pieces of equipment were adapted, including the EMS Synthi A portable synthesiser, a pair of standalone white noise generators created many years ago by Howard Tombs, a mobile talkback unit and a buffer amplifier box originally produced by Technical Services. The XLR-LNE connectors on Ray Riley’s Timecode Memory Units weren’t removed: they just received a warning label. Some devices, such as the ARP Odyssey synthesiser were fitted with an IEC mains inlet connector.

By now, IEC mains distribution boards had also been installed on the engineer’s benches. To avoid leaving mains-powered equipment unattended, remotely-controlled IEC mains panels were also fitted into Brian Hodgson’s office. These were connected to his computer equipment and hi-fi system.

Even composers now had to attend safety courses. Elizabeth Parker, escorted on her way to such a course by Roger Limb, unfortunately fell over a pot-hole inside the underground car park! Around this time the author also went on a safety course, just six months before his final departure.

In the autumn of 1990, the Workshop gained Room 33, a small area located behind the main Maida Vale ‘plate room’, and formerly used by Radio Projects. It also contained much junk, some of which was found to be useful, and was eventually used as a cable store. At the same time, Room 11, formerly used as a studio, was converted into a computer room and office area for the author.

Early in 1991, the old Radiophonic Library area, located between the main Maida Vale ‘plate room’ and Studio D, was converted into an equipment store. Formerly used for storing archived sound tapes, it was fitted out with a large amount of racking for the storage of old and obscure devices. During this operation, Ray Riley disposed of over two hundred reels of quarter-inch recording tape, whilst the Deltalab DL4 Digital Delay Line and other obsolete equipment was sent away for auction. Meanwhile, in Studio A, the old jackfield and trunking were finally removed. A simple microphone connection box was then installed, allowing the room to be used as an acoustic recording area.

By October of 1991, the old Studio D installation was also dismantled, although the Soundcraft 1624 console, now ten years old, was retained for a short time. Early in 1992, the room was fitted out with the Soundcraft Series 200 8-channel mixer, allowing it to be used for copying and experimental work. A year later, the video copying facility from Room 10 was also moved into this area.

Around this time, Phase II of an impressive plan to redevelop the Maida Vale studios was announced. However, in the light of Producer Choice this was soon abandoned!

©Ray White 2001.