Three-quarters of my time at the Workshop was spent working on television programmes. In the early 1990s the BBC started to do more collaborations with other broadcasting organisations to share programme costs, especially in the case of more expensive productions.

CRACKING THE CODE

For an eight-part television series about the mapping of the human genome, I was invited to write the music. This was a collaboration between the BBC and WGBH (Boston).

From the outset I realised there could be some problems for me. American and British taste are very different. This was made clear from the outset, as we called the programme 'Cracking the Code.' and WGBH called it 'The Meaning of Life.'

I had to compose each music cue twice and make three versions of the signature tune, as the original graphics were not liked.

There was about thirty minutes of music in each episode, with only just enough time allocated to me to make one version of each cue. Shown below is an example of the same music cue as composed for the BBC and WGBH. It is designed to cover a sequence about the near-extinct national bird of Hawaii - the Nene.

At this time I owned my own Digital Audio Tape (DAT) recorder [made by Sony] and thought it wise to keep backups of all the music tracks. It is from these tapes that the following are compiled:

1. Titles (UK), DNA, Boy running from war,

Titles (USA), Boy running, Eugenics, Japanese internees

2. Twinsburg March (UK)

3. In a dark place/Prehistory, DNA

4. Twinsburg March (USA)

5. Virus made safe, 'Flu grinds you down!'

6. World War 1, Inside the egg-chick development

7. Time passing, Fish eggs, DNA, Birds, Insects, Animals

8. Ritual of Life, Hawaii and Silver sword plant,

Iceland and German Team

9. Gentle baby: Link

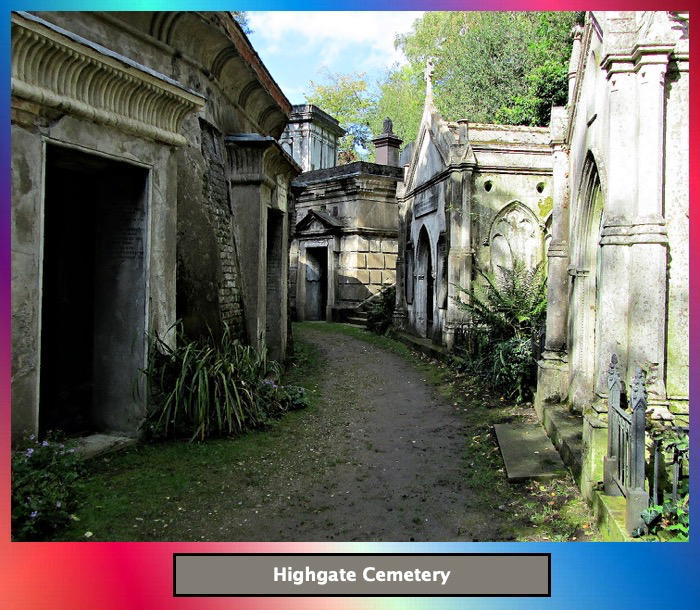

10. Brazil and Graveyard

11. Respectability, Water and Schistosomiasis

12. Africa, Malaria mosquitoes, Dead Africans

13. Slime mould walking, Nematodes

14. Eat Beef!!! Cow's stomachs, China, Grow the corn

15. Fun dancing in Romania

16. Strange sheep - safely grazing

17. Blood, Emergency spare part surgery, Sad longing, Mouse milking, Many strange mice

18. Dance band (USA), DNA,

Sad introspective version of main theme

19. Romanians and Alzheimer's disease, Debbie (piano solo)

20. London

21. DNA, Chimp and child, Serious thought

22. Twinsburg (USA), DNA

23. End credits (UK)

24. End credits (USA)

The tracks are unaltered and not re-mixed for easy listening. Much of what occurs is prompted by visual cues: e.g. In the Twinsburg sequence (USA version) each time the bells chime there is a visual cut to a different pair of identical twins.

[This was the last series that Malcolm worked on.]

SETTING SAIL

At a Creative Radio Committee meeting I put forward an idea to make a documentary feature about the business of death. Coincidentally Piers Plowright, a Radio Drama Producer, had a similar idea. It was agreed that we should collaborate and make the programme at the Workshop.

We didn't rush this, regarding it as a relaxing job to do in our spare time. We met from time to time whenever we had some new material to discuss. After two years, we thought we ought to try and put something together, otherwise, we joked, we might become featured in the programme ourselves.

I was making some final adjustments to the programme one day, when I realised that we had something good here, but it wasn't quite right. I decided to do what I had done many times before, and seek the help of an innocent ear. Max Early was on attachment to the Workshop at that time and over lunch I asked him if he could spare me an hour of his time that afternoon to listen to the programme that we had called 'Setting Sail'.

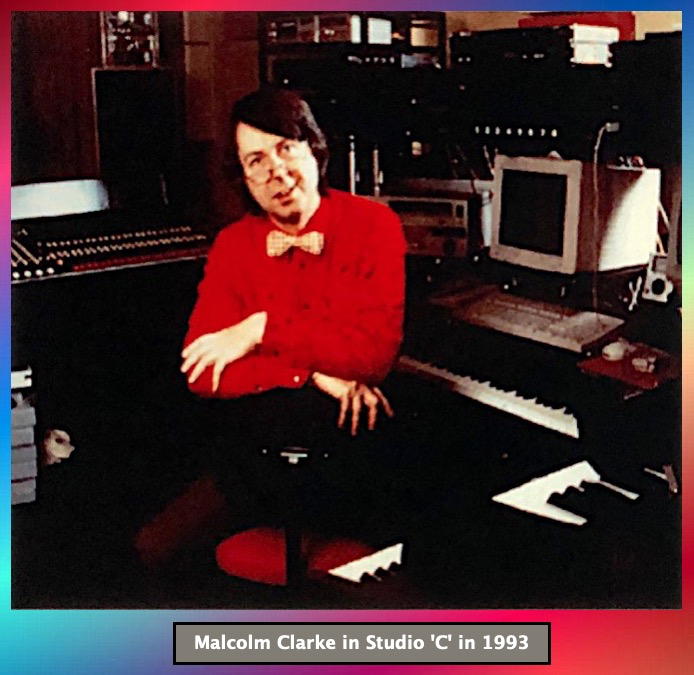

He agreed, and that afternoon in Studio 'C' he listened very intently to the programme. At the end, I asked him what he thought and he said a few complimentary things, and then went on to say what a marvellous opening the end would make. "What about moving the beginning to the end then?", I joked. "Why not?", he said. Suddenly, I realised this resolved the structural reservations I had about the piece, and by the end of the afternoon 'Setting Sail' was finished and ready to be launched.

Of all the programmes I have produced, this has been one of the most successful. It is simply put together, but in a very Radiophonic way. I think the magical quality that the programme has is perhaps due to the unhurried way in which it was made. It is a programme that is regularly rebroadcast world-wide and has won several prizes, one of which was the ultimate award in broadcasting, The Italia Prize:

In 1995 I took early retirement from the Radiophonic Workshop. Less than a year later, the BBC decided to close the Workshop for financial reasons. Very quickly all the Workshop studios and rooms were emptied, as under the new system of 'total costing' a rental was charged on any area which was occupied in any way.

The tape library was partially emptied, but when one of the 'Doctor Who' enthusiasts enquired as to the availability of the 'Doctor Who' sounds and music, an arrangement was made whereby all this material was made available to the Whovian society. Some of the library was rescued and catalogued, but I have found it very difficult or impossible to find certain programmes. To my annoyance, I couldn't find 'Setting Sail'.

I knew that this programme was regularly rebroadcast, but a copy could not be found. Eventually, I found a copy on a low-grade Philips cassette. It sounded awful and there was a cricket commentary, in reverse, induced over most of it. By adjusting the playback head azimuth [the angle of the playback head to the tape] the quality improved a little, and raising the head slightly stopped the cross track induction. 'Setting Sail' was then enhanced using the computer program 'Sound Forge'. It is now an acceptable copy and is the version used here:

OH, SALVADOR DALI

Since my retirement from the BBC in 1995 I have been once again interested in the visual arts. What I really find exciting is the fusion between sound and image that has been made possible by the development of the Personal Computer (PC).

When composing music for broadcasting or film, it was nearly always the case that the visuals were presented to the composer in their complete fine-edited form, and it was this visual structure that dictated the form of the music. As the time elements in a visual strand are not normally critical, it would seem to me that in most cases it is better to edit the film to the music. Stanley Kubrick understood this, and I'm sure that the success of Ken Russell's early films was due to the fact that he used music sequences, uncut or altered in any way, and choreographed them with visual images (Russell is a trained dancer).

If art is the architecturisation of white space, it is important to remember that space is timeless. With this definition in mind, music could be described as the architecturisation of white noise within time. It is in the placing and refining of the random eliments of noise-chaos which gives us sound in the first place, and where music will always be a slave to time. Cutting picture to sound must be preferable, as the visual framework is always elastic, while the structure of music, framed within the precision [of] time, can move very little and only in certain places, if the building is to stand!

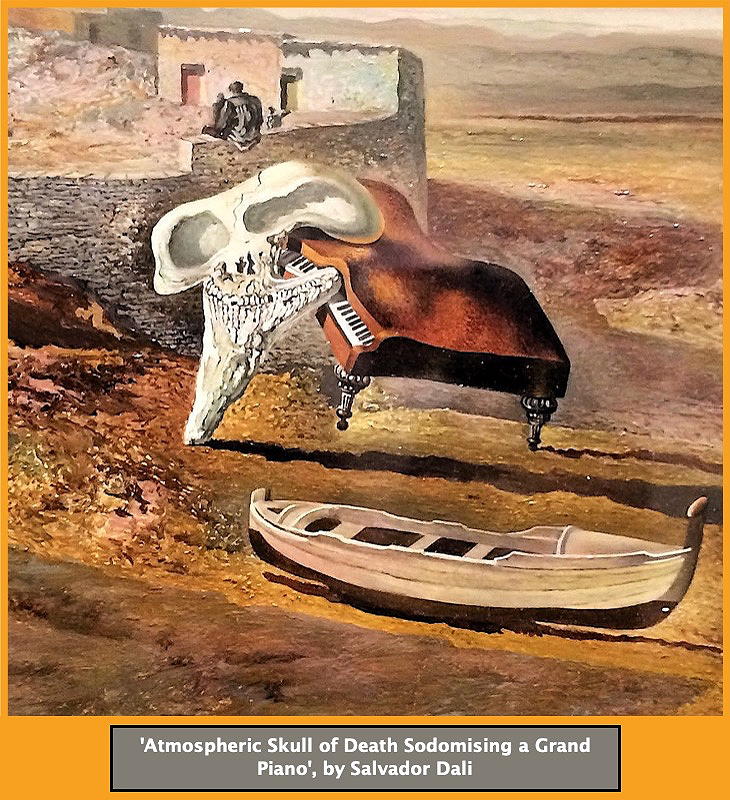

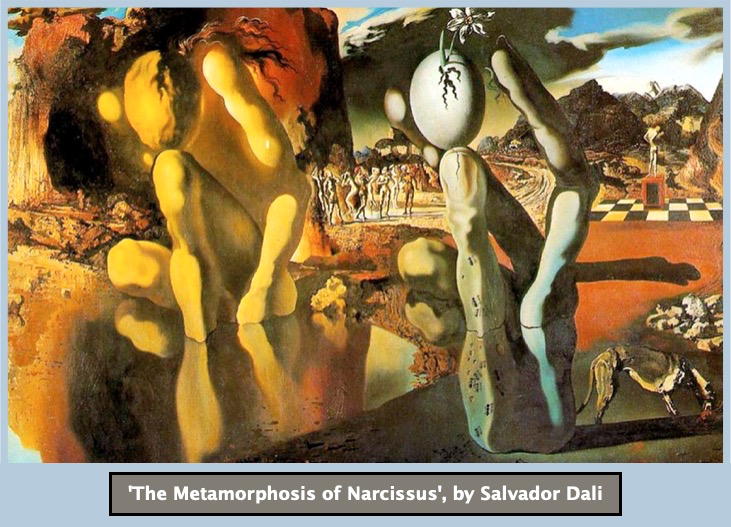

For my first experiment I chose the paintings of Salvador Dali as inspiration.

My intention then is to make an audio-visual experience that is in the first place structured by the sound track. With both sound and image being composed and generated within the same computer, everything remains fluid. One painting, 'The Metamorphosis of Narcissus' is examined in detail. It is occasionally transformed and provides most of the visual content. These ideas have now expanded and a wide range of images, both original and from other sources, are being employed. At the moment, only half the visual track is complete, and so I include the sound track only, and ask you to imagine your own images based on the above ideas.

The piece is called 'Oh, Salvador Dali!'. Near the end, a love poem written by the Spanish playwright Lorca, to Dali, is set as a song and is sung by Ann Gall. When we were recording the song, Ann asked me what its tempo was. It told her it was intended to be free and up to her to decide, and that I wasn't worried about the key either, as I hadn't yet written the accompaniment. Rather like the problem of applying music to picture, song with accompaniment always seems to be a bit of a balancing act, and here was an opportunity to avoid this.

As Gerald Moore, the accompanist, put it -

When I came to map out what Ann had sung, I was surprised how much the tempo had varied. I am certain, however, that this variation is an important element in the interpretation, which a pre-composed setting would have constrained.

'Poem to Dali' by Lorca, Sung by Ann Gall

Oh, Salvador Dali with your olive voice!

I say what your person and your pictures tell me.

I do not praise your imperfect adolescent brush,

But sing the firm direction of your arrows.

I sing the beautiful striving of your Catalan lights,

Your love of whatever has a possible explanation.

I sing your tender astronomic heart,

Made of French cardpacks and unwounded.

But above all I sing the common thought

Which joins us in the dark and golden hours.

Art is not the light that blinds our eyes.

First of all its love, or friendship, or just fencing.

POSTLUDE

On April 1st 1997, thirty-nine years after it had opened, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop closed.*

[*Other sources indicate the official closure was actually on this date in 1998.]

Why this happened is very complex, and the complete details might never be revealed. What follows is enough to show that something was seriously wrong.

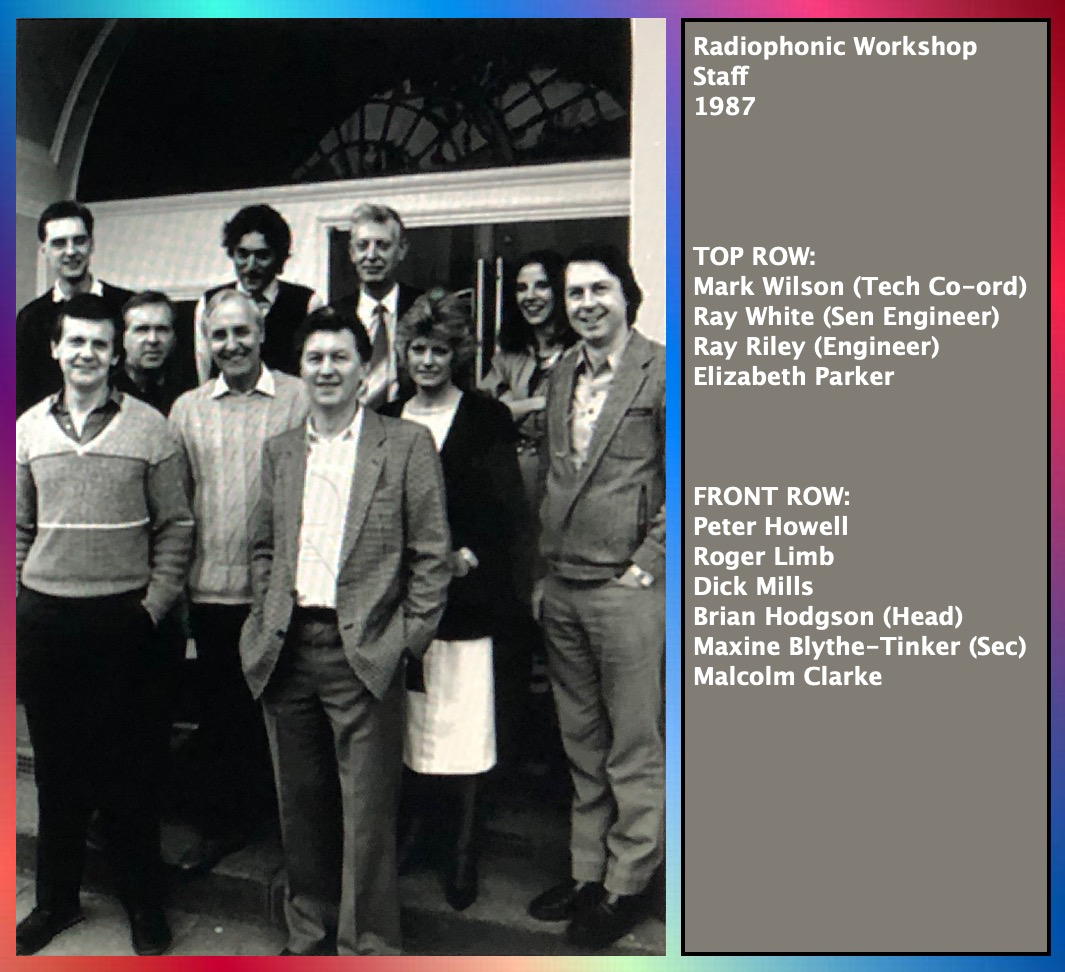

We first became aware of a 'sea change' in the BBC when, in 1987, Michael Checkland, a senior BBC accountant, opened one of our new studios. A week later, the newly appointed Chairman, Marmaduke Hussey, sacked the Director General, Alister Milne, and made Checkland the new DG (We now had an accountant as DG!)

Soon afterwards, as Hussey reveals in his book 'Chance Governs All', he brought in John Birt to help 'tame' News and Current Affairs. In 1991 Birt became DG, but Hussey found he was unable to control him and 'by 1996 Birt had brought the BBC to the brink of creative breakdown.'

Under Birt the BBC was run on the Thatcherite principle of 'monetarism'.

In 1992 the Workshop was told that it was no longer a 'resource' [a core part of the BBC], but a 'service department' [also known as a 'business unit']. This meant that we were to be fully costed - what we charged our customers should balance against our overheads. We cut back wherever possible, to the extent of doing without a Head of Workshop (to save a salary). The odds, however, were stacked against us. Most of our overheads were fixed (accommodation and services). It became clear that the Radiophonic Workshop, which had been originally set up as a creative and experimental department, could not survive as a business.

It hadn't been conceived to make a profit and would never do so.

©Malcolm Clarke 2003

MALCOLM'S TELEPHONE DEMO

This demonstration tape shows the range of music and sounds that Malcolm could create.

To see a full list of the programmes worked on by Malcolm Clarke, please click here. When you've finished, press your browser's 'Back' button.

VIDEOS

OBITURIES

Daphne Oram

A TRUE ARTIST

It is with great sadness that I write of the passing of one of the most creative and inventive thinkers of modern times. Daphne Oram, the co-founder of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, passed away on January 6, aged 77.

Daphne introduced her formative ideas to me when I was an average music student at Christ Church College, Canterbury, and how she changed the way I perceived sound and music. Her influence led me into the BBC and ultimately into sound dubbing and composition. l am fortunate have been her student, following in the footsteps of Isao Tomita, Brian Eno and Carl Heinz Stockhausen. Daphne created an experimental early intelligent musical instrument called Oramics, inspiring the modern electronic music industry of today.

This charming, eccentric individual, who appeared at the college gate with her shopper trolley filled with oscillators, bits of electronic circuitry and a quarter inch tape machine, leaves behind a legacy of imaginative alternative thinking as an inspiration to all composers from all musical genres. She very much wanted to remain until her dying day a 'useful' member of society. A true artist in the fullest sense of the word.

She leaves her brother John, nephew Chris and niece Carolyn.

Paul Wilson

©Paul Wilson

Delia Derbyshire

by Brian Hodgson

Guardian Obituary, Saturday 7 July, 2001

In 1963, soon after joining the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Delia Derbyshire, who has died of renal failure aged 64, was asked to to realise one of the first electronic signature tunes ever used on television. It was Ron Grainer's score for a new science fiction series, Dr Who.

Grainer had worked his tune to fit in with the graphics. He used expressions for the noises he wanted - such as wind, bubbles, and clouds. It was a world without synthesisers, samplers and multi-track tape recorders; Delia, assisted by her engineer Dick Mills, had to create each sound from scratch.

She used concrete sources and sine- and square-wave oscillators, tuning the results, filtering and treating, cutting so that the joins were seamless, combining sound on individual tape recorders, re-recording the results, and repeating the process, over and over again.

When Grainer heard the result, his response was "Did I really write that?" Most of it, Delia replied. She deserved at least half the royalties, insisted the composer. She did not get them. At that time the BBC preferred to keep members of the workshop anonymous and uncredited.

Shortly after Delia had arrived at the workshop in 1962, I was also invited to join. I was stunned by her beauty, awed by her talent, and we began a friendship and a working partnership, within the BBC and outside, which was to delight and infuriate us for 40 years.

Delia was born in Coventry and educated at Coventry Grammar School and Girton College, Cambridge, where she took a degree in music and mathematics. After briefly working for the United Nations in Geneva, she joined the BBC in 1960 as a studio manager.

In those days BBC career progression was a slow affair, but before long she was sitting in, off-duty, at the new Radiophonic Workshop in Maida Vale. The senior studio manager, Desmond Briscoe, realising that the tall, quiet, auburn-haired young lady was not only enthusiastic but enormously creative and talented, invited her to join the department on attachment; she was to remain until 1973.

Delia used, he realised, an analytical approach to synthesise complex sounds from electronic sources. "The mathematics of sound," he said, "came naturally to her."

Delia thought that perhaps she just had a very strange mind. She analysed everything: the pace, the cutting, the editing of a film, every inflection, every comma, the subtleties in the human voice. "I suppose in a way," she observed, "I was experimenting in psycho-acoustics."

Although Dr Who made Delia and the Radiophonic Workshop nationally famous, it was her other drama and features work that showed her true talent. Her collaborations with the poet and dramatist Barry Bermange for the Third Programme showed her at her elegant best.

He put together The Dreams (1964), a collage of people describing their dreams. It was set by Delia into a background of pure electronic sound. In a second 1964 Bermange piece about people's experience of God and the devil, Amor Dei, he asked her to create a gothic altarpiece of sound. She composed this with snippets of archive and voices, again with only the simplest of equipment and facilities, often working through the night, for weeks on end.

Among her outstanding television work, one of her favourites was composed for a documentary for The World About Us on the Tuareg people of the Sahara desert. It still haunts me. She used her own voice for the sound of the hooves, cut up into an obbligato rhythm, and she added a thin, high electronic sound using virtually all the filters and oscillators in the workshop. "My most beautiful sound at the time was a tatty green BBC lampshade," she recalled. "It was the wrong colour, but it had a beautiful ringing sound to it. I hit the lampshade, recorded that, faded it up into the ringing part without the percussive start.

"I analysed the sound into all of its partials and frequencies, and took the 12 strongest, and reconstructed the sound on the workshop's famous 12 oscillators to give a whooshing sound. So the camels rode off into the sunset with my voice in their hooves and a green lampshade on their backs.”

In those days, the Radiophonic Workshop received a stream of visiting musicians, composers and writers - from Berio to Brian Jones - and she entranced them with her intellect and the joy of her company. But Delia was never starstruck; she cheerfully devoted as much time to encouraging young students as to talking with celebrities.

In the mid-1960s she and I worked with Peter Zinovieff, the composer and visionary pioneer of synthesisers, in a company called Unit Delta Plus. Delia became involved in an early electronic music concert at the New Mill Theatre in Newbury that also featured a pioneering light projection show by Hornsey College of Art and magnetic sculptures by Paul Takis.

She worked on Guy Woolfenden's electronic score for Peter Hall's 1967 Royal Shakespeare Company production of Macbeth with Paul Scofield, and on Hall's film Work is a Four Letter Word (1967). It was at Zinovieff's Putney studio that she first met Paul McCartney.

Later, Delia, her protege David Vorhaus and I set up Kaleidophon, a Camden Town-based independent studio. There she worked on the album Electric Storm (1968), now considered a classic, which was credited to White Noise and released on Island Records.

At Kaleidophon we put together electronic music for the London theatre of the late 1960s. There was Medea and Alan Dobie's Macbeth for the Greenwich Theatre; On the Level, a musical by Ron Grainer; and Tony Richardson's Hamlet at the Roundhouse.

She also took part in a Roundhouse concert of electronic music including early electronic works by McCartney. She even recorded a score for an ICI- sponsored student fashion show, which was the first in the world to use electronic music.

Her 11 years and nearly 200 programmes at the workshop represented probably the most productive times of her life. They also took their toll. To work with Delia during the late 1960s and early 70s was to witness the joy and energy-sapping pain of creation. "I think I must have reverse adrenalin," she said. "As the deadline gets closer most people speed up - I just get slower."

By 1973 Delia had become progressively more unhappy with her life at the workshop and she left to join me at Electrophon, an electronic music studio I had set up in Covent Garden. There, unfortunately, she found little relief from her unhappiness and decided to leave London. She became involved, bizarrely, in the laying of the national gas main as a radio operator, she worked in a Cumbrian art gallery, and she worked in a bookshop.

In 1980 she met Clive Blackburn, who was to be her partner for the rest of her life. Probably for the first time, she found happiness and settled into what, for her, was a normal existence.

For others it still appeared to be organised chaos - yet she did have a tidy and organised mind. She was still fascinated by the act of creation; still encouraging, scolding and praising her many friends.

In the last few years she was beginning once more to take an interest in electronic music, encouraged by a younger generation to whom she had become a cult figure. The technology she had left behind was finally catching up with her vision.

One night many years ago, as we left Zinovieff's studio, she paused on Putney bridge. "What we are doing now is not important for itself," she said, "but one day someone might be interested enough to carry things forwards and create something wonderful on these foundations." Her partner survives her.

Delia Derbyshire, composer and arranger, born May 5 1937; died July 3 2001

©Guardian News and Media Limited