'August 2026: There Will Come Soft Rains' was first broadcast on Radio 4 and was well received. Steven Hurst, then Head of Radio 3, phoned me and asked why I hadn't offered it to his network. I said that I thought it would be a good idea to repeat it on Radio 3, and he agreed. After this transmission, I was invited to attend the programme review board. Here again, it was well received and the board were interested to note that it had a universal appeal, working well with a wide-ranging audience.

NEDERLANDSE OMROEP STICHTING

The European Broadcasting Union (EBU) Drama Conference was that year to be hosted by Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (NOS, the Dutch Broadcast Foundation) in Amsterdam, and 'August 2026' was chosen to be the production for discussion. I attended as lecturer and was overwhelmed with the demand for copies of the programme, and by the Dutch hospitality.

I visited the NOS Dutch broadcasting centre at Hilversum and was very impressed by their technical facilities, which were mostly provided by Philips, a local manufacturer. It was surprising that 'dub editing' was used for all tape editing (copying from tape to tape and dropping in and out of record to achieve a join). This was nowhere near as accurate as physically cutting and joining the tape, but did mean that the tape was reusable.

I didn't see any microphone stands. These, I realised, were unnecessary, as all microphones were permanently attached to long pantographic arms, which hinged out from cupboards around the studio walls (good for security).

When I looked into the large music studio cubicle [the term 'cubicle' in the BBC refers to the area of a studio that contains the mixing desk], I couldn't understand why there were so many microphone channels. This became clear when the engineer pointed out that every stringed instrument had its own microphone. These were [Sony] ECM 150s, the small lapel type, and were clipped onto the bridge of each instrument. The engineer faded out all sound but one violin. He then faded in another violin and pointed out how they were not in tune or time with one another, but on adding gradually more instruments everything seemed to average out and the sound became very rich.

This was a useful lesson for me when synthesising sound from multiple oscillators. Synchronisation [of oscillators], which seemed to be the want of most synthesiser designers, would be last thing I was looking for.

'THE ORIGINS OF CAPITAL'

Martin Esslin, then Head Of Drama, perhaps encouraged by the success of 'August 2026', set up the 'Creative Radio Workshop'. This met bi-monthly and was open to any member of staff who wanted to offer new and original programme ideas.

After the first meeting, Martin asked me if I would be interested in producing a new dramatic work, which was being written by an American, Philip Oxman. I agreed, and Martin offered to bring Philip over to the RWS as soon as the script was complete.

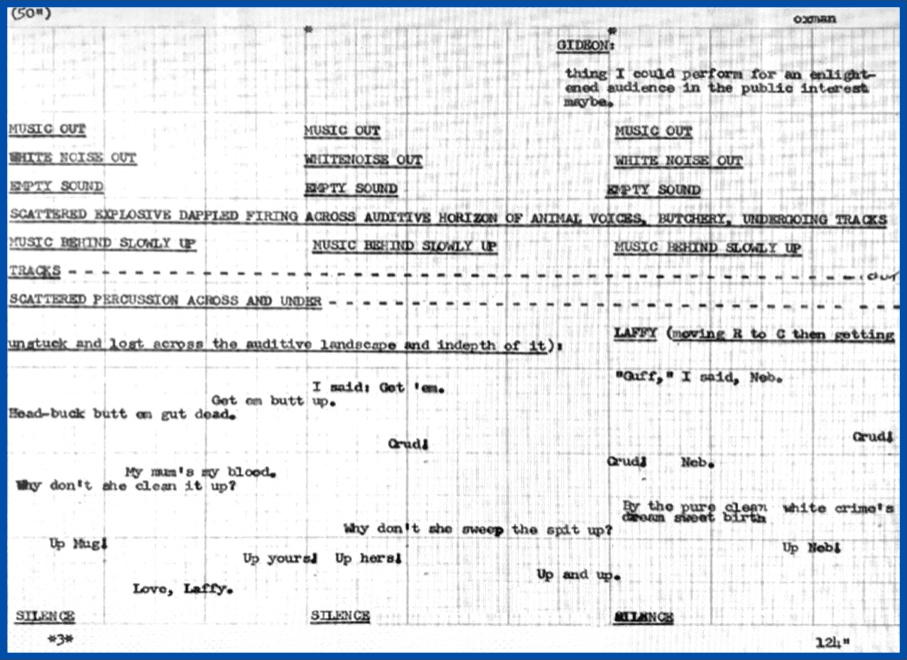

We met a few weeks later, and I was amazed when Philip presented me with the script. It was called 'The Origins of Capital and the Descent of Power', and weighed over twenty pounds [9kg]. It was written entirely on sheets of graph paper, about two feet by three feet [60cm by 90cm] in size, and had illustrative sections made on Polaroid* colour-plate transparencies.

[* The Polaroid company invented the instant camera in 1948.]

Each actor's voice and sound was meticulously plotted on the grid to enable split-second timing. Philip described it as:-

It was an experiment in creating an intricate structure of poetic imagery in words and sounds, rather than telling a dramatic story in a conventional way. Oxman's story was of a circus family, so poor that they have to butcher the animals that the customers come to see: the sawdust ring is both the circus ring and the butcher's killing floor.

Philip suggested that I might like to come and stay with him at his house for a few days so that we could get to know one another - very important when undertaking a project like this. He gave me directions to get there which sounded unreal:

The house was a huge mill-house built of honey-coloured Cotswold stone and mentioned in the Domesday Book. Philip was keen to show me his newly-refurbished top floor. This he had opened up into one massive long room with a lovely maple floor. It had a Japanese feel about it in its simplicity. There were a few chairs, a clavichord, a grand piano (Oxman's partner Lisel was a pupil of Yvonne Loriod, the wife of the composer Olivier Messiaen) and a beautiful wooden model of 'Theatre in the Round', set up as a circus.

We talked for long hours, and then Philip said: "We better get to bed, I've planned an exciting day for tomorrow. I've put you in the bedroom next to the millrace. Its sound will soon lull you off to sleep!" I've never had a better night's sleep.

When I awoke, I could hear Philip talking on the telephone. He had phoned the local American Air Force base. "Hello, it's Philip here", he said. "I hope you're not going to be making any noise with your planes today. I've got a friend here from the BBC and we're going over to White's to do some recording." It seems that silence was agreed and later we set off to White's, armed with a Uher portable tape recorder [a high quality German machine, first made in 1961].

White's was the local village butcher. It was an old-fashioned butcher's shop with a slaughterhouse round the back. "I'm glad you're early," said Mr White, "we've got a couple ready to put down out back and they get a bit nervy." "What about me?", I thought. The recording session went well and the sounds were instantly absorbed into the BBC Sound Archives and the Sound Effects Library. When we left, Mr White gave us some green Gammon 'for your tea'.

Back at the mill-house, Philip threw the gammon into the largest frying pan I've ever seen. It just fitted on top of the wood-burning Aga cooker. Only two other things joined the gammon - half a jar of ginger marmalade and some home-grown 'button' Brussels sprouts. It all caught fire, but the result tasted perfect.

[An excerpt from the completed programme appears below:]

After its first broadcast [in 1974], at the Programme Review Board, Martin Esslin, no stranger to experimental radio himself, called it 'One of the most way-out and daring things we have ever done.' Critic Peter Vansittart described it as:-

I produced many new plays at the RWS in the years to come, and these proved to be very popular in America, where radio drama was undergoing a renaissance. Perhaps this was due to the fact that they were denied the exclusive radio experience that we had enjoyed during the war years.

FM SYNTHESIS

Following the introduction of voltage-controllable devices, many new synthesisers burst onto the market. These became more and more complex and very large and heavy - for example the Yamaha CS-80:

A big breakthrough came when it was realised that the well-known process of frequency modulation (FM) could be simply applied using voltage-controllable devices.

FM synthesis is a reatively simple way of making complex sounds. When several devices are interconnected, to frequency modulate one another, the results rapidly become very complex. Many learned papers have been written on this subject, maintaining that the system lent itself to creative synthesis. Perhaps the most famous of these was by John Chowning of Stanford University, California. In his introduction he demonstrates how, with only two devices, it is possible to produce a predictable waveform output. For example, two sine waves can generate something similar to a square wave, which sounds similar to a clarinet.

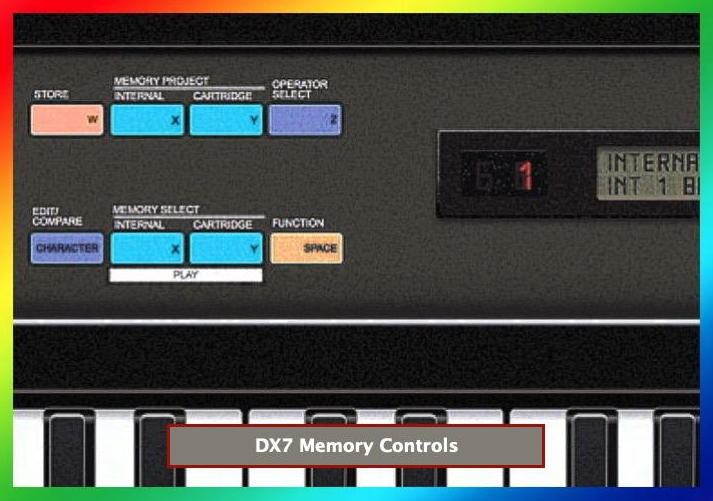

When, however, I received the new Yamaha DX7 FM synthesiser, I soon discovered predictability beyond two operators was not possible, and the DX7 used six operators (FM devices) arranged in varying configurations called algorithms. A small change to any device could have incredible and unforeseeably complex results.

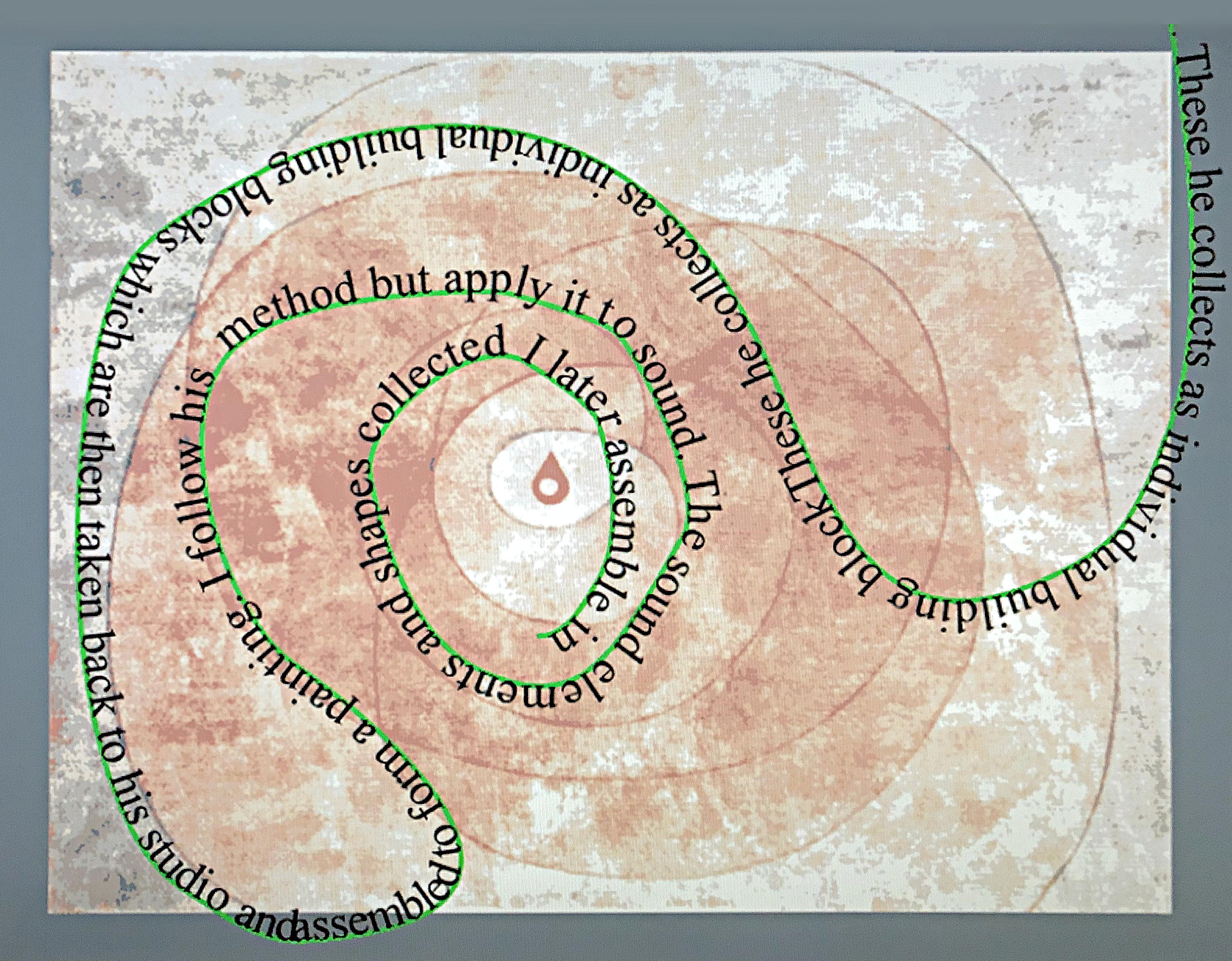

The only way I could program an FM synthesiser was to play with it until it produced a sound I thought might one day be useful. I would then store the sound in a database library and give it an accurate descriptive name, which would help me find it again, should the need for such a sound arise.

FM sounds are very direct and can sound almost more real than the real thing, especially if the sound is of a percussive nature and without any internal resonance or acoustic. One of the first sounds I made was one of this type. It sounded similar to a metallic elastic band being twanged. By delaying the overall pitch change rate and extending the envelopes with a random control, I found the effect this sound produced, when a melody line was keyed in, was comical. It sounded like each note was a frenetic scrambling attempt to be accurate, but failing in a very human way. Inspired by this sound, for my first FM piece I arranged part of Rossini's 'William Tell Overture':

SAMPLING

Towards the end of the 1970s, small personal computers were becoming more powerful. Their processors [and those in synthesisers] were faster and, perhaps more importantly, RAM (random access memory) was getting bigger and less expensive. Having larger memory available made possible the 'sample sound' synthesiser.

This was based on the idea that real sounds could be digitally stored in memory and replayed from that memory at different pitches by varying the playback sample rate. These synthesisers rapidly became more complex, adding looped sound, so that the notes could be sustained as long as required. When the note [on the keyboard] was released, the sampled decay sound of the note was appended. 'Velocity sample' switching was introduced, so that an appropriate sound sample for the same note played quietly [piano] or loudly [forte], for example, could be used [automatically]. Also envelope shaping, filtering and modulation were added.

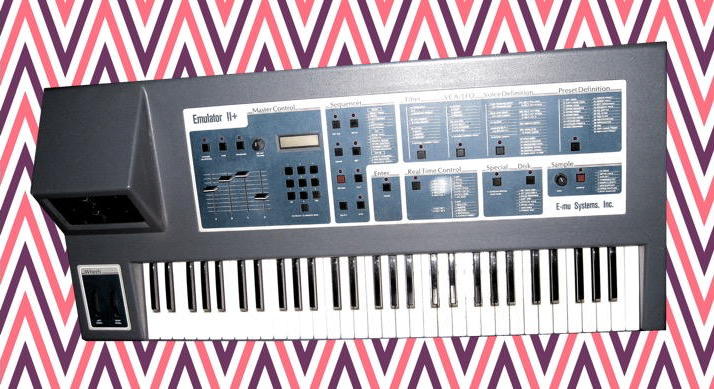

My first sampling synthesiser was an Emulator II by E-mu Systems Inc. This stored its sampled sounds on five-and-a-quarter inch floppy discs. It was housed in a crude grey plastic case and was shaped like the robot dog in 'Doctor Who' - 'K9', which is what it became called.

To test the Emulator II, I looked for a live sound to record which would reveal its sampling capabilities. From my days as an engineer, I knew that the [Broadcasting House] control room 'sound multiple' [a system in which sound sources and studios could be dialled up via a numerical code] contained 'Big Ben' on code 'D00'. This was a live microphone housed in the tower of Westminster [known as the Elizabeth Tower since 2012]. I arranged a feed of this to my studio and sampled all the four quarter-chimes and the hour strike.

I was pleased with the result and decided to weave a musical theme around the chime samples to check its playback response.

By coincidence, News Department asked the RWS if we had any copyright-free music which they could play down the sound line from their studio in Westminster. They would use this to identify the line and instantly confirm its quality. I offered this new piece and it was recorded onto an endless loop tape. And there it is to this day [in 2003], constantly repeating itself and yet heard by only one or two people!

'IT'S AMAZING'

I used 'K9' (the Emulator II) for the first time on a signature tune for Children's Television. The director told me all about the programme, which was called 'It's Amazing', and asked if it could contain computer game sounds. These sounds I made on a small home computer, which had only 3.5KB of memory, called the VIC-20 [made by Commodore].

The sounds were ideal for the programme, but the VIC-20 could only manage to generate one at a time. The solution to this problem was to sample them into 'K9'.

When I had finished the signature tune I phoned the director to ask if he would like to hear it. "Ah," he said, "I haven't told you have I? The title has changed from 'It's Amazing' to 'Believe It or Not'". I pointed out that I had composed it to scan with the rhythm of the title. When he heard it, he liked it and said we didn't need to worry about anything as subtle as just a programme title change.

Some weeks later, I was showing my two young children around Television Centre, when I noticed that 'Believe It or Not' was in the studio. As it was an audience show, I arranged seats for them. I then went into the control cubicle to see how things were going. Silence greeted me. "Oh Malcolm," said the director "I haven't told you, have I? We're not using your signature tune. Richard Stilgoe is introducing the programme and he has written one for us." The signature tune [called by its original name, 'It's Amazing'] was never used and it gets its first airing here.

To my surprise, a month later the director or 'Believe It or Not' phoned and told me that he was about to go into the studio with a new programme called 'It's Amazing'*. He needed it in two days time and could I help? I was so surprised, I said "yes".

[*Malcolm's text is confused here, as the recording for this new programme is always known as 'Believe It or Not'.]

That morning I took a tea break and sat with some of the brass section from the Radio Orchestra. I told them I had a signature tune to complete in two days, and did they have any ideas? The best idea was to do something like the famous trombone solo called 'The Acrobat'. We discussed trombonists and I mentioned how remarkable was the trombonist with 'Spike Jones and His City Slickers'.

'I can do that' said Eddy Lorchin. 'You just have to put your tongue into the cup of your mouthpiece and wiggle it about while you are playing.' I asked him if he was free that afternoon to record and he said "yes". I quickly wrote out a fun tune, which Eddy recorded employing his special technique in the middle section.

The accompaniment to this was done very simply, by recording myself making tongue-clicking noises, with flutter-feedback and a lot of bass cut, very close to a PGS microphone [a BBC ribbon microphone, introduced in 1953]. The trombone line was doubled with itself an octave lower using an MXR pitch changer [Model 129 Pitch Transposer]. This produced a virtuoso tuba-like effect. I worked on through the night and it was all completed and sold by lunchtime.

LOUDNESS & FUN

We were always trying out new devices for treating sound. One that I thought that I would never use was the compressor. This had become very popular with pirate radio [broadcasters], as it brought the constant sound level up to maximum, thereby saturating the transmitter and extending the area of its coverage. For a section in the eight-part television series called 'Love Law', the director asked me for an arrangement of its gentle signature tune. This, he told me, was for a section dealing with nightlife in Tokyo, and should be as loud as possible.

The Emulator II sampling synthesiser enabled us to orchestrate any sound that could be recorded. In the first part of the next example, I was asked to make all the music for the play 'Frankie's Monster' sound as though it was being played on bubbles. The bubbling sound sample was made by blowing air through a straw dipped into milk. This alone did not have a strong enough fundamental [frequency] to support a tune, so it was combined with a sine wave, which tracked the pitch voltage from the keyboard along with the sample.

In the section following, made for 'The Demon Headmaster', I was asked to arrange the music for 'Dick Barton' [Special Agent Dick Barton first appeared on the Light Programme in 1946]. The BBC's Sheet Music Department couldn't find this, so it had to be transcribed from an archive recording of the programme. The producer requested that it should be OTT ['over the top'] with 'bells on'. It was certainly fun to do, as I hope it is to listen to (I have yet to add bells!!).

'FATAMORGANA'

In 1983 a comprehensive exibition of the sculptures of Tinguely was held at the Tate gallery. I had for a long time been fascinated by his musical approach to sculpture and decided to make a programme about him. Unfortunately, at the moment, the programme tapes are lost,* but I am able to include a short example from one remaining make-up tape. This clearly shows the close affinity between sound and image, which is the essence of Tinguely's work.

[*The Radiophonic Workshop's Tape Library document for the year 2000 does not include this programme. The BBC Genome indicates that a Radio 4 broadcast of 'Kaleidoscope', dated 7 September 1982, reviewed Tinguely's exhibition, and it is assumed Malcolm's work was for this programme.]

RADIO & ART

When I came to compile the complete list of programmes that I had worked on at the RWS, I was surprised, when I looked at my own radio productions, how many of them appeared to be visual subjects and therefore seemingly more appropriate to television. Of these programmes there was a whole series about the work of painters.

These included:-

Stanley Spencer, The Venetian School, Dali,

Sir Roland Penrose, Klee, Cedric Morris,

Constable, William Blake, Tingueley and

Van Gough in London.

JOHN CONSTABLE:

'I SHOULD PAINT MY OWN PLACES BEST'

One of the first programmes I worked on at the Workshop was for Schools Radiovision. These programmes were designed to be recorded, off air, by the school.

To go with this taped programme was a set of colour slides and a script indicating where these slides were to be shown. When the programme was finished we took it to a school in Paddington to assess it with a class of children.

Here I learnt something important. When a slide was held on screen for some length of time, so that they could study it, their concentration was maintained as long as the soundtrack was sustained. If the soundtrack stopped their concentration stopped. It was as if the soundtrack stopping threw a switch, telling the brain to prepare itself for something new.

I spent the next few days filling all silences over slides, however small, with sound.

I have just discovered, today, August 21, 2003, a small makeup tape of the music I composed for the Radiovision programme, 'Constable'. This is the earliest example of my work at the RWS I have found. I enclose a short section of this below:

I wonder how any of us managed to make anything with just three tape recorders, a portable mixer and a very old Albis audio filter.

PAUL KLEE:

'GOING FOR A WALK WITH A LINE'

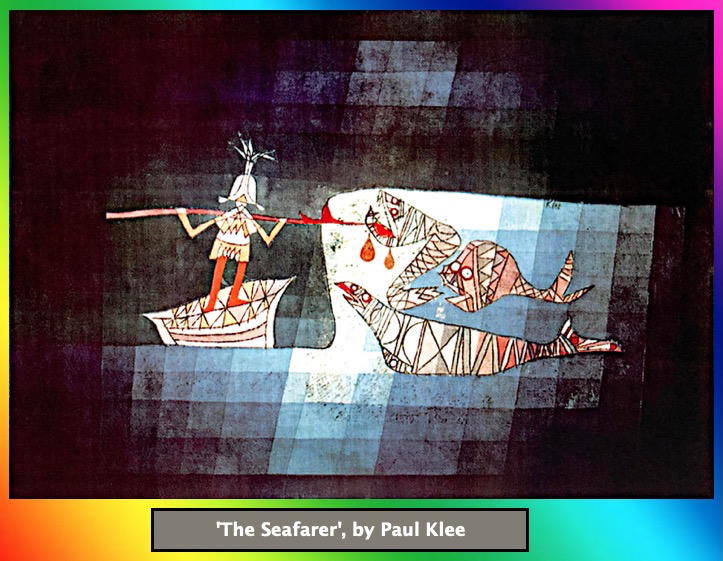

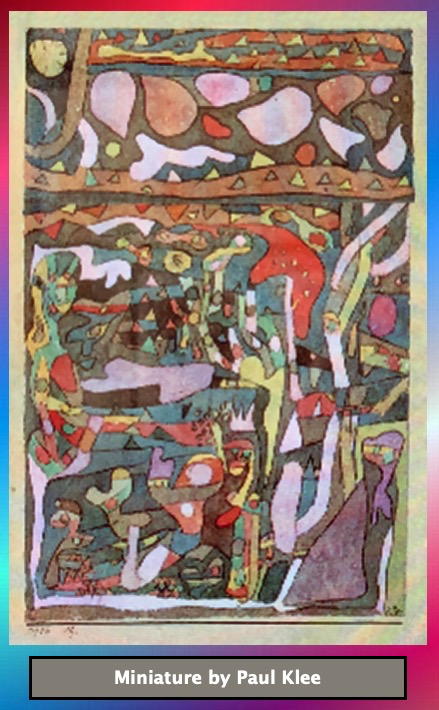

Of all the artists I made programmes about, Paul Klee was closest to my heart.

As a youth, he had set out to be a professional musician playing violin in the Berne Symphony Orchestra and violin or viola in his own quartet. His wife was a professional pianist.

At the age of twenty he decided to take up painting and, although this was his main interest, he still earned a living by playing the violin. He also started to write and produced many volumes, the most important of which dealt with his theory of art.

He was also a poet and had many works published. Klee, in fact, intermingled the musical and the poetic with the pictorial. He described himself as being at a crossroads - a meeting place of intuition.

In his book 'The Thinking Eye', he describes his structural method as 'going for a walk with a line'. This I understand as being a sort of disciplined doodling. Later on in the book he reveals his method of formulating a painting. He takes us on a walk in the country and here he observes a range of objects and shapes. In the following example from the programme, we join Klee, 'going for a walk with a line':

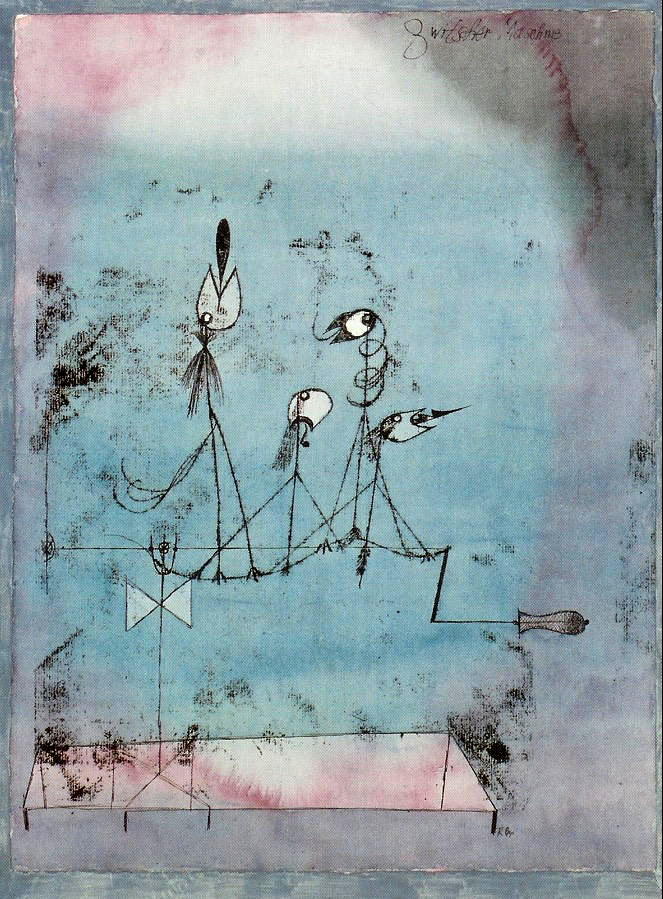

Klee called one of his paintings 'The Twittering Machine'. This was a typical piece of Klee whimsey and contained Swiss-inspired cuckoo clock-like mechanisms.

He later used this painting as an inspiration for a poem, which he also called 'The Twittering Machine'. Here is that poem as it was set in 'Going For a Walk With a Line':

©Malcolm Clarke 2003